Learning about Microbial Communities on Cheese Rinds with Rachel Dutton

Rachel Dutton visited UC Davis to deliver a presentation highlighting her work on microbial communities using cheese rinds as models. Dutton is a Bauer Fellow at the Harvard FAS Center for Systems Biology. As part of the prestigious Bauer Fellow program, Dutton works in her lab alongside postdoctoral researchers on an independent project to study the microbial communities of cheese rinds.

Dutton's visit to UC Davis in August coincided with the 2014 American Cheese Society annual meeting in Sacramento, where she also spoke about her exciting work on the microbiology of cheese. Dutton's talk at the Robert Mondavi Institute was titled, "Cheese rinds as model microbial communities,” and highlighted work from a recent publication in the journal Cell with co-authors Benjamin E. Wolfe, Julie E. Button, and Marcela Santarelli. Their feature article was also covered by Christina Agapakis on the Scientific American blog.

In her talk, Dutton explained that because microorganisms live as part of multi-species communities, we can no longer only study them in isolation. However, we know very little about what microbes do within those multi-species communities, which exist everywhere and impact the health of every ecosystem on our planet. The major challenge of studying microbial communities is that they are incredibly complex.

In order to examine this different paradigm for understanding microbial function, Dutton and her team use cheese rinds as a model to ask questions about microbial interaction, changing physiology, and the underlying principles of microbial community formation. Cheese rinds are easy to access and manipulate, and are composed of rich surface-associated communities of bacteria. Moreover, Dutton explains that her lab has the added benefit of learning from the thousands of years of knowledge passed down from cheese makers on how best to manipulate these microbial communities.

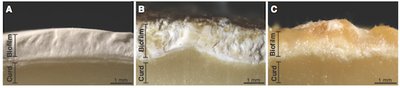

Dutton and her lab set up a series of experiments to determine how microbial communities differ across different types of cheese rinds: washed rinds, which are "washed" in a salt water solution; natural rinds that form on the cheese without human manipulation; and bloomy rind cheeses inoculated with specific bacteria or fungus.

Of the 137 types of cheese sampled, Dutton and her lab identified an average of seven bacterial genera and three fungal genera per cheese. They found that there is a common pool of "cheese-loving microbes" found anywhere, but that changes in the microbial communities depend on the environment the cheese maker is crafting on the surface of the cheese. They found patterns in microbial communities corresponding to rind type, which was heavily effected by moisture. The team found that moisture is an important driver of community diversity, and that certain organisms strongly correlate with moisture, while others especially do not.

The team plans to continue research in community relationships between bacteria and fungi through "in vitro" cheese making. Their initial look at the collected cheese rind samples revealed that fungi appear to be driving particular interactions within the community, as bacteria seem to be highly reactive to the presence of certain fungi.

Dutton's cheese rind research intends to shed light on how we might observe and understand microbial communities. The broader impacts suggest that their methods might translate to less tractable communities, like human skin. This might also lead to ways to manipulate microbial communities to improve human health, the environment, and our food systems.